The historical context

The pace of change in communications technology means that GCHQ constantly faces new challenges. We need an innovative workforce able to keep up with technology trends if we are to continue to keep Britain safe and protect the government's official communications. This is an enduring aspect of what we do, and was as true in 1914 as it is today.

The invention of British Signals Intelligence, 1914

While there was no organisation in the UK responsible for producing intelligence from intercepted communications prior to 1914, the need to protect British official communications was already understood. This meant that there was at least an implicit understanding of what might be possible. During the Boer War, the Army had some success in reading encrypted messages, but the impetus was to detect efforts to evade censorship. Consequently, this did not lead to the establishment in the UK of anything permanent though plans to repeat the process if the UK went to war again were put in place.

If the War Office's preparations for making use of Signals Intelligence in wartime were minimal, there was even less consideration in the Admiralty. One member of the Naval Intelligence Division, Fleet Paymaster Rotter, had devoted some time and effort in an attempt to break encrypted German Naval messages between 1910 and 1912. His lack of success only served to confirm the gloomy predictions of senior officers that encrypted messages would never be read.

Although the story told of British Signals Intelligence in the First World War focuses mainly on the work of Room 40 in the Admiralty, it was in fact MO5b (later MI1(b)), an intelligence section in the War Office which had the first success against German codes. This was largely due to the fact that the French, who had years of experience of Signals Intelligence against the Germans, were prepared to share all that they knew.

MI1(b) did not really develop as an integrated Signals Intelligence Centre as the Army preferred to have units exploiting intercepted communications locally, at the General Headquarters on each of the Fronts.

Soon after the outbreak of war, Sir Alfred Ewing, Director of Naval Education, was invited by the Director of Naval Intelligence to lead the Admiralty's effort against enciphered German naval communications in Room 40. He drew together a small team of German speakers. Although they had no initial success against German encryption, their work in sorting and classifying the intercepted messages they received laid the foundations for traffic analysis. This would prove eventually to be as valuable a tool for Signals Intelligence as for those trying to break encrypted communications: intelligence was produced by studying the external signs showing the way in which the Germans communicated.

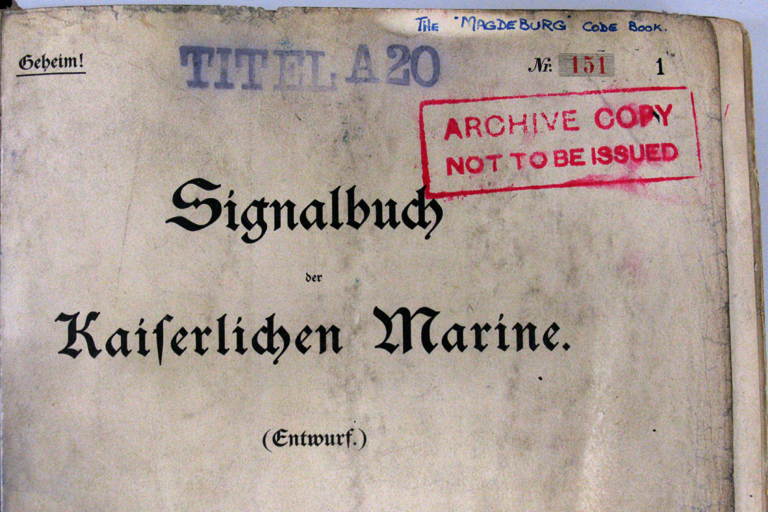

Room 40's work to break encrypted communications was also kick-started into success by an ally: the Russian Navy found copies of the German High Sea Fleet codebook on a German Light Cruiser, the Magdeburg, and sent one to London. After a few days' work, the system used by the Germans to re-encipher the messages was worked out and Room 40 began to provide a quick turnaround service of decrypted messages.

The Magdeburg Code Book. ©Crown Copyright 2014/TNA - ADM 137/4146

Although both the Admiralty and War Office were producing decoded German messages by the end of 1914, their Signals Intelligence organisations were still immature. The need to protect this valuable new source of information was felt to outweigh the value of using it: the Battle of Jutland might have been a decisive victory for the Royal Navy if its commanders at sea had access to the same information as Room 40 had. And the experience of codebreaking had no immediate effect of improving the security of the Royal Navy’s or Army’s own communications.

Nevertheless, we can look at the Admiralty and War Office as they stood at the end of 1914 and see the first shoots of what would become a permanent Signals Intelligence organisation in 1919, and grow into the GCHQ of today.